-… ..- .-. .-. .. – — .— ..- … – .. -.-. .

In 1853, the first telegraph line was strung in California. James Gamble, the man in charge of the “wire party”, wrote a marvellous account of running the line down the peninsula and up to Sacramento. Here’s a rough map showing where the lines went.

It should come as no surprise that the telegraph was almost stopped by @KarlTheFog:

Our little party worked energetically, and on the first day we strung up about three miles, camping for the night at what was known as the Abbey, a wayside house on the outskirts of the city. The next day we made about six miles, having commenced early in the morning and working until dark. The day had been a very foggy one, and as the country at that time was but sparsely settled, and but little land fenced in any direction, we found ourselves, when the day’s work was over, lost in the fog. Toward the close of the day, and shortly before leaving off work, we had noticed, as we came along, a squatter’s cabin, to which, having no tent with us, we had decided to return and seek shelter for the night. To find this cabin was now our great desire, that we might be protected from the cold winds and fog. Separating, but with the understanding that we should keep within hailing distance of each other, we groped in the dark and fog for more than an hour, but without success. The squatter’s cabin seemed to be a sort of befogged “Will o’ the Wisp”–with this difference, we were sure that it was there somewhere, but to save our lives none of us could find it. We finally determined to give up the search, roll ourselves up in our blankets, and make the best of it on the ground.

Luckily the march of technology was saved when James & friends bumped into the cabin while looking for firewood (in September), saving themselves from the dreary grey fate of Karl sapping their very will to live.

Seriously though, it’s hard to appreciate just how isolated San Francisco was in that era. The fastest Clipper ship from New York took 89 days. It was just 30 days if you cut over through Panama or Nicaragua (if you wanted to risk dying of malaria). Overland from Iowa was about three months. The Pony Express didn’t start until 1860 and took 10 days from Missouri (but it only ran for 18 months, cost about $125 per letter adjusted for inflation, and shut down 2 days after the transcontinental telegraph lit up in October 1861). The transcontinental railroad wasn’t completed until 1869.

Another way of looking at it — the people of San Francisco were so isolated they actually got excited about talking to people IN SAN JOSE. I mean, that’s pretty isolated. Consider that the cost for a telegram was 75 cents for 10 words, and 25 cents per 5 words after that. Adjusting for inflation, that’s about $21 for the first 10 words, and $7 for the next 5 words. Assuming a 140 character tweet is 25 words, that would run you $42 per tweet.

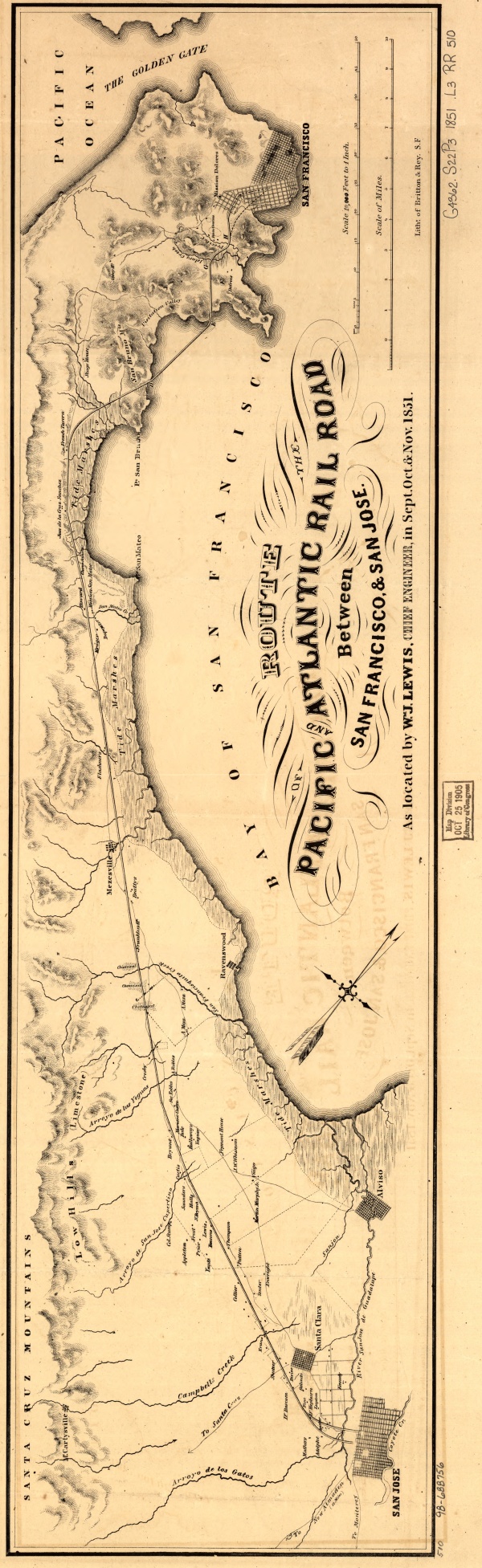

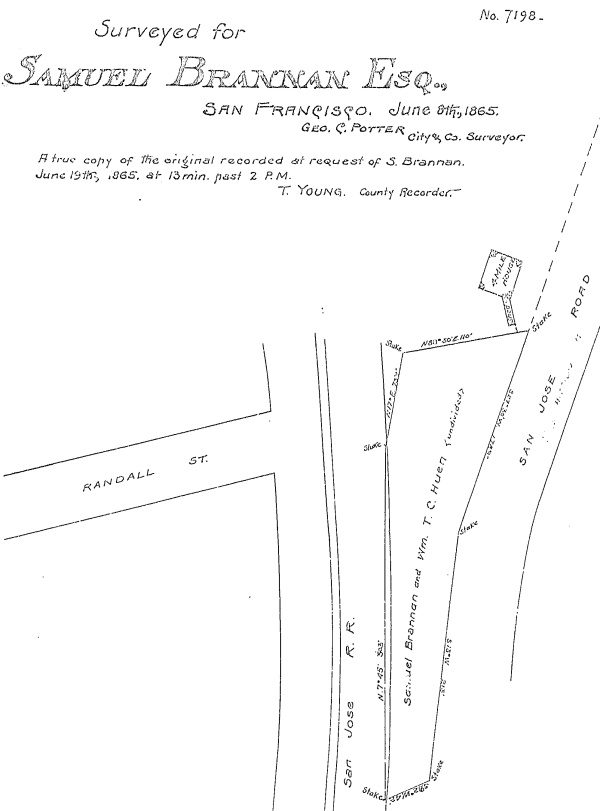

“The Abbey” that they refer to is visible in this rather ridiculously awesome 1851 map of the proposed rail route between San Francisco and San Jose (rotated for your viewing pleasure.)

Note the proposed path skipped the Bernal Cut and suggested a Bayshore route, aka Caltrain today.

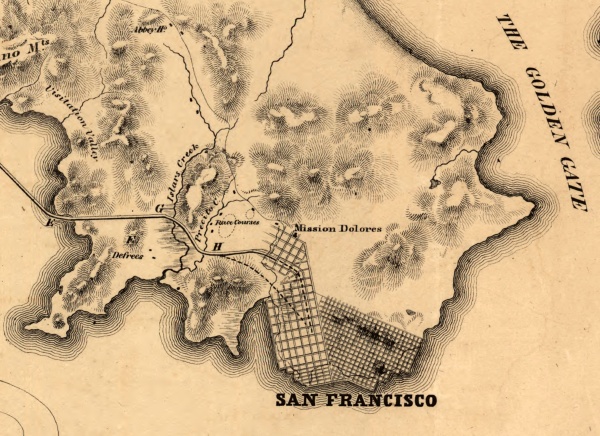

Zoom and enhance — “Abbey Ho!” (That line is the road to San Jose.)

I see the Pioneer and Union race tracks! And Bernal! And Precito Creek! And Islars Creek!

I’m pretty sure the building between the forks of Precita creek is the Bernal Adobe. (Oh man, do I want a picture of that.)

This glorious map was part of a report made by William Lewis, the Chief Engineer of the Pacific and Atlantic Rail Road Company, which eventually built the railroad to San Jose in 1860-1864. The full report was published in the Dec 25 1851 edition of the Daily Alta, though the letters on the map aren’t referenced — fortunately for you, dear reader, I found them described on pages ii and iv of this version of the report.

I’m not sure what year the plan for the bridge was abandoned and decision was made to dig the Bernal Cut, but you can read about it in this interesting progress report from Nov 1862. (For reference, the Bayshore cutoff was built from 1903-1907.)

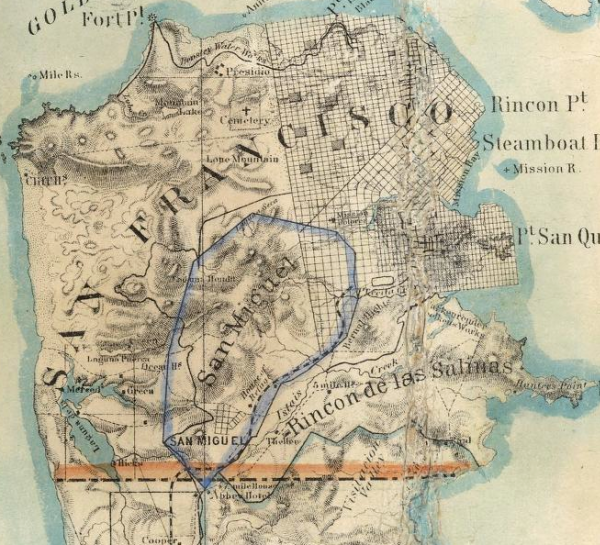

The Abbey is still visible in this 1867 map of the Bay Area via David Rumsey (at the bottom of the blue San Miguel outline), just outside the current city limits in Daly City.

It’s crazy to think that just a few miles out of the city, there was little to nothing. Notice the 5 and 7 Mile Houses on the 1867 map — all must have been a big deal in the day. Hope they had beer too.

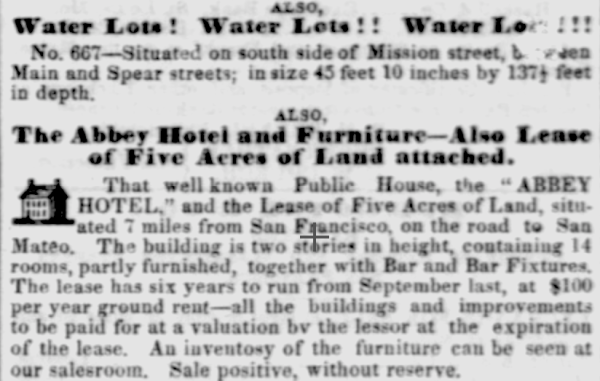

If you were around in 1854, you could have leased the Abbey Hotel for a very reasonable rate. Thankfully there was a bar (and fixtures!)

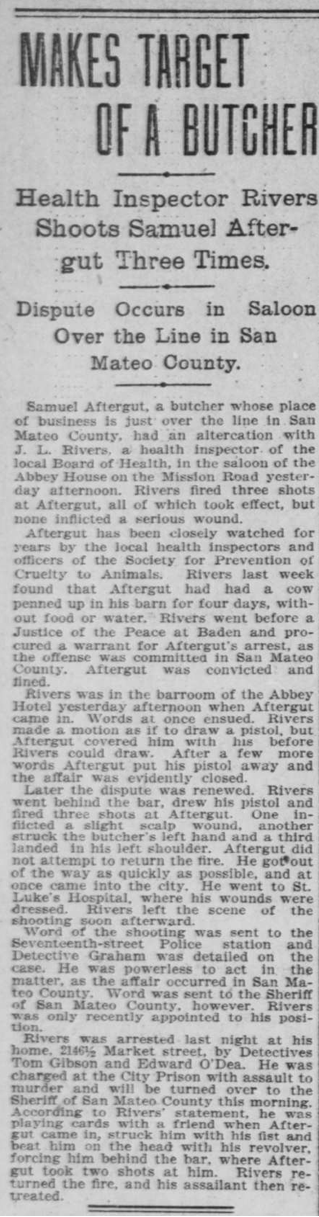

They also had DRAMA. In 1902, health inspector Rivers shot at a butcher, Samuel Aftergut, three times in the bar room of the Abbey. (Thanks @sfhistorian!) Note that the butcher had been on watch by the SPCA.

Man that is not going to help the Abbey’s Yelp score.

There was even a 4 Mile House between Mission and San Jose Ave on Randall (where the Shell station is).

Needless to say, I was surprised to find references to A STABBING AFFAIR and to MURDER in the Four Mile House:

1867:

1889:

So maybe we skip drinks at the Four Mile House and the Abbey.

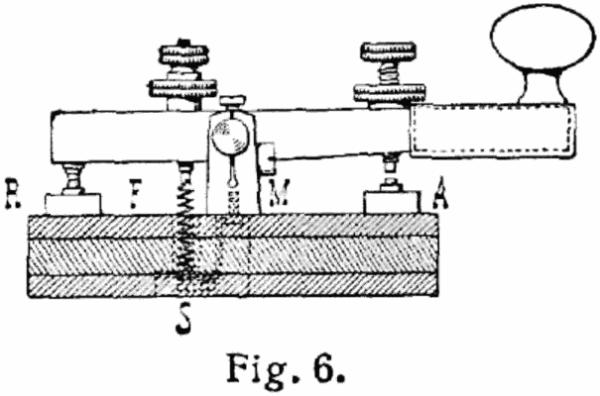

Speaking of telegraphs, you may have heard that after 150 years, India shut down its telegraph system in July. End of an era! Last telegram in the world! In fact, there was a such a fierce competition to send the very last one a week-long backlog built up.

Great story, except that telegrams as Samuel Morse would recognize them died out quite a while ago. As Ars Technica notes, what’s actually being discontinued by the Indian government is their Telex service.

Samuel Morse’s version of telegraphy—Morse code over the wire—died a long time ago. It was replaced by Telex, a switch-based system similar to telephone networks, developed in Germany in 1933. The German system, run by the Federal Post Office, essentially used a precursor to computer modems and sent text across the wire at about 50 characters per second. Western Union built the US’ first nationwide Telex, an acronym for Teleprinter Exchange, in the late 1950s.

Telegraphy really didn’t stand a a chance against the fax machine and text messaging. That being said, the Telex is alive and well in many countries.

“Italy still has a printer and Telex line in every post office,” said Stone. “And people still send loads and loads of telegrams there. It’s a state-run telegraph service, so I don’t know if it’s profitable or not. But it’s exactly as the service was run in India and the same as it’s been for 50 or 60 years.”

I guess there is something to be said about a message with legal standing from an established authority that you can wave around in front of someone. See McLuhan, medium vs message.

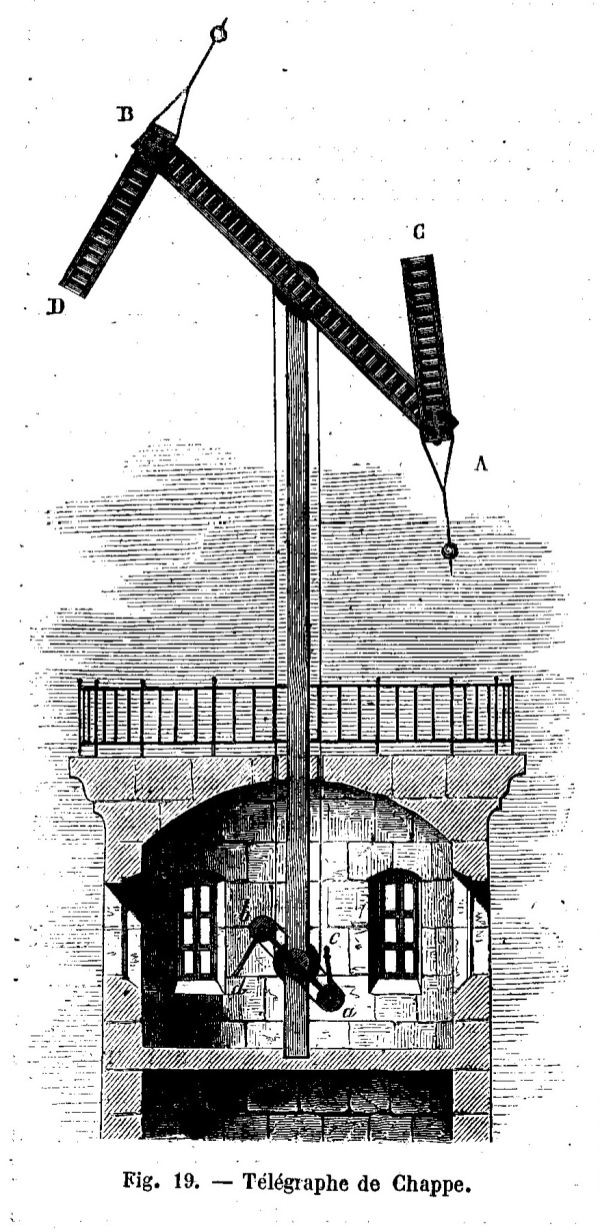

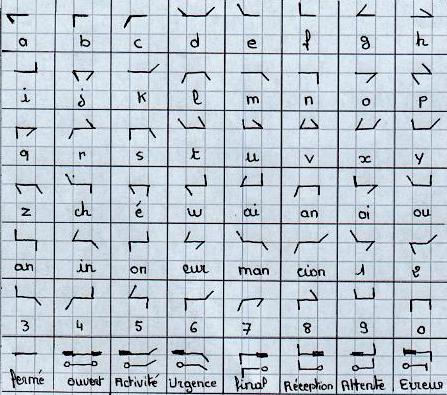

Of course, many forget that in the 1850s, electrical telegrams kicked the ass of the French optical messaging system, the Chappe Telegraph. It was a semaphore system that used a series of rotating bars and arms to transmit letters.

Here’s the conversion table:

While it could theoretically send a system from Paris to Toulon in 12 minutes, messages tended to take longer, if they got there at all that day.

“When rates were measured in the 1840’s, only two out of three messages were found to arrive within a day during the warm months, dropping to one in three in the winter.”

And it didn’t work at night. (Must… refrain… from… Corey… Hart… joke…)

But apparently it gave rise to a French idiomatic expression:

Basically the formation of a signal was done in two steps and three movements (the French expression “en deux temps et trois mouvements” still meaning today “rapidly done” comes from it).

But it worked well enough for 50 years.

Here’s a nice little piece from the BBC on some guys trying to restore one of the stations. And here’s a paper that covers its development, along with some of the encoding and error corrections systems they developed. And an early 19th century topographic map showing one of the stations.

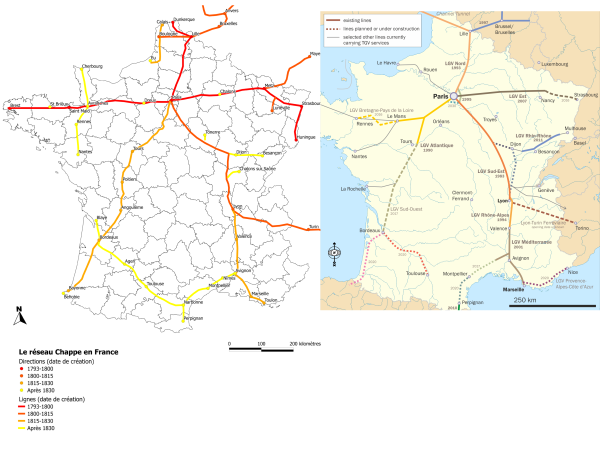

The system was extensive, and bears a (frankly unsurprising) resemblance to the French high speed rail network.

These maps from Wikipedia show construction dates for both systems.

(It seems any large network in France takes 40 years to build.)

Telegraph systems were built extraordinarily quickly around the work, and in 1850, the first cable was laid across the English Channel (though it got cut by fishermen the night after it was completed). After failures in 1858 and 1865, a cable crossed the Atlantic in 1866.

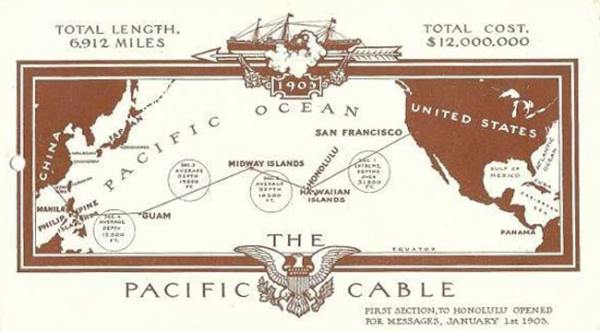

A fascinating account of the first transatlantic cable is covered at atlantic-cable.com, along with the trans-Pacific cable that landed in San Francisco in 1902.

Also via atlantic-cable.com, guys in hats standing on Ocean Beach (near Fulton):

(If you’ve made it this far into the post, you really ought to read Tom Standage’s “The Victorian Internet”, for it, like he, is awesome.)

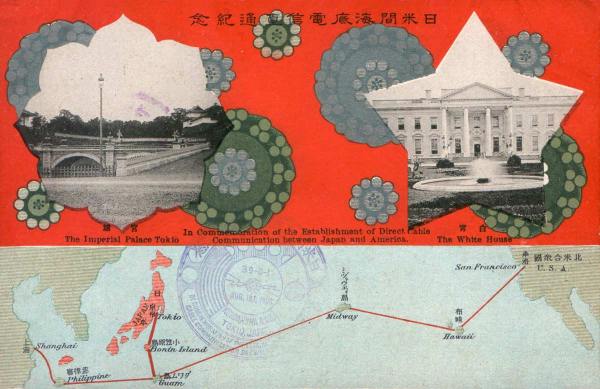

The Pacific Cable was big in Japan.

A little research and adjustment for inflation shows that it cost FIFTY OR MORE DOLLARS A WORD to send a telegram from Osaka to San Francisco in 1903.

Think of that when you Skype your buddies overseas.

Side note: I was surprised to see that San Francisco was written in kanji on the map above.

“Foreign” places are typically written in katakana, e.g.

サンフランシスコ

but on this map it’s written as “Mulberry Harbor”.

桑港

Turns out that’s from an old Chinese transliteration of SF:

Since you’re asking, SF has been written as “old gold mountain” in Chinese since the Gold Rush.

旧金山

Anyway, this naturally leads to one of my favorite subjects, telecommunications networks taken out by animals. Eventually, fiber optic undersea cables replaced copper. But to the surprise of engineers and executives, SHARKS STARTED EATING THE CABLES. Said the New York Times in 1987:

Sharks have shown an inexplicable taste for the new fiber-optic cables that are being strung along the ocean floor linking the United States, Europe and Japan, telephone company officials say.

In the Atlantic alone, shark bites have caused the failure of four segments of cable, which is the main artery for global voice and computer communications. And British telephone officials monitoring the installation of the fiber-optic network that will link the United States to Japan and Guam are also reporting troubles with gnawing sharks.

The attacks have caused some delays in laying cable, and a single bite on a deep-sea line, which is about the size of a garden hose, can cost $250,000 or more to fix. There is a benefit, however. In studying ways to limit damage from the attacks, the telephone companies are providing marine scientists with valuable new data on sharks and specimens of previously unknown species.

The first evidence of sharks’ attraction to the cables was the discovery of shark teeth embedded in an experimental line off the Canary Islands in 1985. A shark usually loses teeth when it bites something, and it later grows new ones.

”We were surprised,” said James M. Barrett, deputy director of international engineering for the American Telephone and Telegraph Company. ”We had laid 55,000 or 60,000 miles of undersea cable all over the world with no problem. There had not been a single case of a shark biting one of the old cables,” which were made of copper.

An undersea fiber optic line uses a series of repeaters/boosters. Apparently the sharks are able to detect the electromagnetic field emitted by this line.

Also, the fiber optic cables are much thinner than the old copper cables, making for quite the shark-sized snack.

Don’t believe me? Well, here’s a video OF A SHARK BITING A SUBMARINE CABLE.

And you thought squirrels were bad.

Wow! Great post, tons of awesome information. I had no idea that Visitac(t)ion Valley was such an old name, for one thing.

Also: Bummed that google won’t translate morse code for me.

See http://www.onlineconversion.com/morse_code.htm

yeah, already translated, but I still want google to translate it for me by just dropping it in the search window, dammit.

aaaaah, roger that. I should have figured that out given it was you asking.

Proving that, throughout history, one fact remains the same: fights are always about a chick.

Did I ever tell you about the murder at the Red House at 24th & Mission?

Also, free band name: “A Stabbing Affair”

always those country phoebe’s!

Yowza! another home run!… beautiful work, thanks!

–cc

Interesting that the map shows Sausalito as Sansaulito, and Yegua, which is now known as Mare Island: yegua = mare – female horse.

Didn’t notice that! There seem to be a lot of names that are just one letter off, including Islars and Precito — I wonder if they are translation or transcription errors?

I have a feeling that many place names were never written down until 1849. Did Spain or Mexico ever do a thorough survey or map of the Bay?

I think that “Islars” is an error due to translation. The creek may have originally been named “Aislar”, which of course means to separate or isolate. That would make sense as the Spanish and later the Mexicans would have seen it as water course that separated one area or farm from another. To non Spanish speakers it may have sounded like “Islar”, later Islais. It could have actually been the present tense of aislar, aisláis.

The mapping of the bay(s) is a good question since the Spanish were very thorough in that regard. To the annoyance of the English, the Spanish had already mapped the area around Vancouver by the time they arrived; there’s historical note by an English officer stating that he relied on Spanish maps.

Wow, your Islais theory is an impressive one, I like it.

And I’m very familiar with Spain’s history around Vancouver Island –Captain Quadra & Captain Vancouver actually got along really well: http://www.peruviantimes.com/22/quadra-discoverer-of-vancouver-island-gets-some-recognition-in-his-home-town-of-lima/18241/

Also; Sausalito isn’t a word in Spanish, but sauce is. Sauce is willow. Perhaps afterwards Mexicans, wanting to indicate a diminutive of “sauce”, pronounced it saucelito, and various listeners wrote what they thought they heard as sausalito. A Spanish speaker would pronounce it as Sow-salito, but an English speaker would pronounce it as Saw-salito. The Sansaulito would therefore make sense, because Saul sounds like Sawl in English, but Saool (Saúl) in Spanish, similar to Raúl.

I don’t think there was ever a San Saúl, so later arrivals pronounced and spelled it Sansaulito.

The word “precita/o” has been nagging me, so this is what I think it signifies: If you look at the map, there is “Precita Creek” due north of Bernal Hights[sic]. I think “precita” comes from the word *represa* = dam/resevoir, and that would make sense. A *represa* to control the flow of the creek, perhaps to water livestock, flood control, irrigation, cultivation, etc. Over time it may have been mistakenly written as an incorrect diminutive for represa – reprecita.

Northeast of Laguna de la Merced is Laguna Puerca!

My grandad told me Islais was an ohlon word for clam. With which Islais creek was chock full in the Gold Rush era, and which provided the Old Clam House n Bayshore with its namesake fare.

The best part of that telegraph article is where some yokel outside of San Jose refuses to believe that the telegraph really works, and the work crew eventually wins a supply of watermelons from him in a bet after they successfully prove that they could get a message to San Jose.

—and then there is the whole side story of the Westerfield Mansion….

I love your obsession with historical infrastructure. I too share this obsession but to a lesser due to laziness degree; thanks for writing about it.